[v.1.0] (01/05/2024): Post started!

1. Data Engineering Described

What Is Data Engineering?

A data engineer gets data, stores it, and prepares it for consumption by data scientists, analysts, and others.

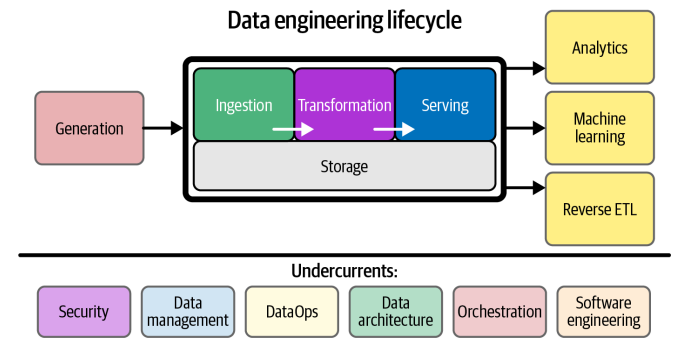

Data engineering is the development, implementation, and maintenance of systems and processes that take in raw data and produce high-quality, consistent information that supports downstream use cases, such as analysis and machine learning. Data engineering is the intersection of security, data management, DataOps, data architecture, orchestration, and software engineering. A data engineer manages the data engineering lifecycle, beginning with getting data from source systems and ending with serving data for use cases, such as analysis or machine learning.

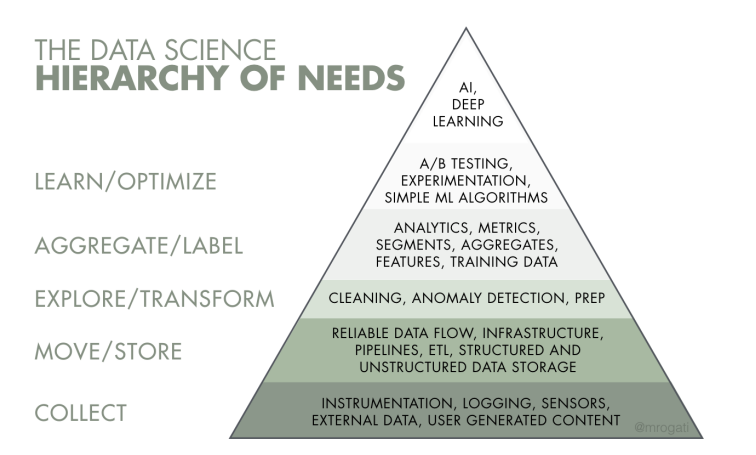

Stage of data engineer lifecycle:

- Generation

- Storage

- Ingestion

- Transformation

- Serving

70%-80% o the time doing the bottom 3: gathering data, cleaning data, processing data. Data scientist aren’t typically trained to engineer production-grade data system.

Data from various sources > Data engineering > Data science and analytics

Data Engineering Skills and Activities

Skillset of data engineering: security, data management, DataOps, data architecture, and software engineering.

Data engineer also care about: Cost, Agility, Scalibility, Simplicity, Reuse, Interoperability.

Data engineer typically does not directly build ML models, create reports or dashboards, perform data analysis, build KPI or develop software application.

Data Maturity & the Data Engineer:

- The data maturity model has 3 stages: starting with data, scaling with data, and leading with data.

- Stage 1: Starting with data

- Here, data engineer is a generalist, do everything.

- Choose the right data architecture.

- Identify and audit data.

- Build a solid data foundationn for future data analyst and data scientist to generate reports and models that provide competitive values.

- Tips:

- Quick win create technical debts.

- Get out and talk to people.

- Avoid undifferentiate heavy lifetying. Don’t box yourself in with unncessary technical complexity. Use off-the-shelf, turnkey solutions wherever possible.

- Stage 2: Scaling with data

- Data engineer here is a specialist, focusing on data science life cycle.

- Tips:

- Establish formal data practices

- Create scalable and robust data architectures

- Adopt DevOps and DataOps practices

- Build systems that support ML.

- Continue to avoid undifferentiate heavy lifting and customize only when competitive advantage results.

- Tips:

- Any tech decisions should be driven by the value they will deliver to your customers.

- Main bottleneck or scaling is not technology by the data engineering team. Focus on solutions that are simple to deploy and manage to expand your team’s throughput.

- You will be tempted to frame yourself as technologist, a data genuis who deliver magical product. Shift your focus instead to pragmatic leadership and transition to next maturity stage. Make sure to communicate with other teams about the practical utility of data and teach the organization how to consume and leverage data.

- Stage 3: Leading with data

- The company is data-driven. The automated pipelines and system created by data engineers allow people in the team to self-service analytics and ML.

- Data engineer need to be more specialize

- Create automation for the seamless introduction and usage of new data.

- Focus on building custom tools and systems that leverage data as a competitive advantage.

- Focus on the “enterprisey” aspects of data, such as data management (including data governance and quality) and DataOps.

- Deploy tools that expose and disseminate data throughout the organization, including data catalogs, data lineage tools, and metadata management systems

- Collaborate efficiently with software engineers, ML engineers, analysts, and others.

- Create a community and environment where people can collaborate and speak openly, no matter theri role or position.

- Tips:

- Once organizations reach stage 3, they must constantly focus on maintenance and improvement or risk falling back to a lower stage.

- Technology distractions are a more significant danger here than in the other stages. There’s a temptation to pursue expensive hobby projects that don’t deliver value to the business. Utilize custom-built technology only where it provides a competitive advantage.

The Background and Skills of Data Engineer

- Data engineer must understand both data and technology. Data engineer must also understand the requirements of data consumers (data analysts and data scientists) and the broader implications o data across the org.

Business Responsibilities

- Know how to communicate with nontechnical and technical people. Pay close attention to organizational hierarchies, who reports to whom, how people interact. Observe!

- Understand how to scope and gather business and product requirements. Know what to build and ensure that your stakeholders agress with your assessments. Develop a sense of how data and technologuy decisions impact the business.

- Understand the cultural foundations of Agile, DevOps, and DataOps.

- Control cost. You will be successful when you can keep the cost low while providing outsized values. Know how to optimize for time to value, the total cost of ownership, and opportunity cost.

- Learn continuously. People who succeed in data are great at picking up new things while sharpening their fundamental knowledge.They’re also good at filtering, determining which new developments are most relevant to their work, which are still immature, and which are just fads. Stay abreast of the field and learn how to learn.

Technical Responsibilities

- SQL: The most common interface for databases and data lakes. After briefly being sidelined by the need to write custom MapReduce code for big data processing, SQL (in various forms) has reemerged as the lingua franca of data.

- We believe that competent data engineers should be highly proficient in SQL

- Python: API, Pandas, NumPy, Airflow, Sklearn, Tensorflow, PyTorch, and PySpark.

- JVM (Java, Scala): Spark, Hive, Druid.

- Bash

2. The Data Engineering Lifecycle

What Is the Data Engineering Lifecycle?

We begin with the data engineering lifecycle by getting dat from source systems and storing it. Next we transform the data and then proceed to our central goal, serving data to analysts, data scientists, ML engineers, and others. In the middle stages, we store, ingest, and transform.

Generation: Source Systems

-

A source system is the origin of data used in the data engineering lifecycle. For example, a source system coule be an IoT device, an application message queue, or a transactional database. Here, a data engineer consuumes data from a source system but doesn’t own or ccontrol the source system itself. Data engineer need to understand the way source systems work, the way they generate data, adn the frequency and velocity o data, and the variety of data they generate.

-

Ex 1: Application DB. Here, applications often consist of many small service/database pairs with microservices rather than a single monolith.

-

Ex 2: IoT swarms. Here, a fleet of devices (circles) sends data messages to a central collection system. IoT are sensors, smart devices,…

-

[IMPORTANT] Evaluating source systems: key engineering considerations

- What are the essential characteristics o the data source? Is it an application? A swarm of IoT devices?

- How is ata persisted in the source system? Is data persisted long term, or is it temporary and quickly deleted>

- At what rate is data generated? How many events per second? How many gigabytes per hour?

- What level of consistency can data engineers expect from the output data? If you are running data-quality checks against the output data, how often do data inconsistencies occurs - nulls where they aren’t expected, lousy formatting.

- How often do errors occur?

- Will the data contain duplicates?

- Will some data values arrive late, possibly much later than other messages produced simultaneously?

- What is the schema of the ingested data? Will data engineers need to join across several tables or even several systems to get a complete picture of the data?

- If schema changes (say, a new colum is added), how is this dealth with and communicated to downstream stakeholders?

- How frequently should data be pulled from the source system?

- For stateful systems (e.g., a database tracking customer account info), is data provided as periodic snapshots or update events from change data capture (CDC)? What is the logic for how changes are performed, and how are these tracked in the source database?

- Who / what is the data provider that will transmit the data for downstream consumption?

- Will reading from a data source impact its performance?

- Does the source system have upstream data dependencies? What are the characteristics of these upstream systems?

- Are data-quality checks in place to chekc for late or missing data?

Storage

- Evaluating storage systems: Key engineering considerations. Here are questions to ask when choosing a storage system for a data warehouse, data lakehouse, database, or object storage:

- Is this storage solution compatible with the architectures’s required write and read speeds?

- Will storage create a bottleneck for downstream processes?

- Do you understand how this storage technology works? Are you utilizing the storage system optimally or committing unnatural acts? For instance, are you applying a high rate of random access updates in an object storage system?

- Will this storage system handle anticipated future scale? You should consider all capacity limits on the storage system: total available storage, read operation rate, write volume,…

- Will downstream users and processes be able to retrieve data in the required service-level agreement (SLA)?

- Are you capturing metadata about schema evolution, data flows, data lineage, and so forth? Metadata has significant impact on the utility of data. Metadata represents an investment in the future, dramatically enhancing discoverability and institutional knowledge to streamline future projects and architecture changes

- Is this a pure storage solution (sobject storage), or does it support complex query patterns (i.e. a cloud data warehouse)?

- Is the storage system schema-agnostic (object storage)? Flexible schema (Cassandra)? Enforced schema (cloud data warehouse)?

- How are you tracking master data, golden records data quality, and data lineage for data governance?

- How are you handling regulatory compliance and data sovereignty? For example, can uyou store your data in certain geographical locations but not others?

Ingestion

- Key engineering considerations for the ingestion phase: When preparing to architect or build a system, here are some primary questions about the ingestion stage

- What are the use cases for the data I’m ingesting? Can I reuse this data rather than create multiple versions of the same dataset?

- Are the systems generating and ingesting this data reliably, and is the data available when I need it?

- What is the data destination after ingestion?

- How frequently will I need to access the data?

- In what volum will the data typpically arrive?

- What format is the data in? Can I downstream storage and transformation systems handle this format?

- Is the source data in good shape for immediate downstream use? If so, for how long, and what may cause it to be unusable?

- If the data is from a streaming source, does it need to be transformed before reaching its destination? Would an in-flight transformation be appropriate, where the data is transformed within a stream itself?

Store

- Key considerations for batch vs stream ingestion

- If I ingest the data in real time, can downstream storage systems handle the rate of data flow?

- Do I need millisecond real-time data ingestion? Or would a micro-batch approach work, accumulating and ingesting data, say, every minute?

- What are my use cases for streaming ingestion? What specific benefits do I realize by implementing streaming? If I get data in real time, what actions can I take on that data that would be an improvement upon batch?

- Will my streaming-first approach cost more in terms of time, money, mainte‐ nance, downtime, and opportunity cost than simply doing batch?

- Are my streaming pipeline and system reliable and redundant if infrastructure fails?

- What tools are most appropriate for the use case? Should I use a managed service (Amazon Kinesis, Google Cloud Pub/Sub, Google Cloud Dataflow) or stand up my own instances of Kafka, Flink, Spark, Pulsar, etc.? If I do the latter, who will manage it? What are the costs and trade-offs?

- If I’m deploying an ML model, what benefits do I have with online predictions and possibly continuous training?

- Am I getting data from a live production instance? If so, what’s the impact of my ingestion process on this source system?

Transformation

- Key considerations for the transformation phase

- What’s the cost and return on investment (ROI) of the transformation? What is the associated business value?

- Is the transformation as simple and self-isolated as possible?

- What business rules do the transformations support?

Serving Data

- Business Intelligence: BI marshals collected data to describe a business’s past and current state. BI requires using business logic to process raw data.

- Operational Analytics: Operational analytics focuses on the fine-grained details of operations, promoting actions that a user of the reports can act upon immediately. Operational analytics could be a live view of inventory or real-time dashboarding of website or application health.

Embedded Analytics: Businesses may be serving separate analytics and data to thousands or more customers. Each customer must see their data and only their data. An internal data-access error at a company would likely lead to a procedural review. A data leak between customers would be considered a massive breach of trust, leading to media attention and a significant loss of customers.

Major Undercurrents Across the Data Engineering Lifecycle

Security

- Give users only the access they need to do their jobs today, nothing more.

- Knowledge of user and identiity access management (IAM) roles, policies, groups, network security, password policies, and encryption are good places to start.

Data Management

- Data governance engages people, processes, and technologies tio maximize data value across an organizationn while protecting data with appropriate securiyt controls.

- Discoverability: End users should have quick and reliable access to the data they need to do their job. They should know hwere the data comes from, how it relateds to other data, and what the data means

- Metadata is data about data and it underpins every section of the data engineering lifecycle.

- Data accounrability: means assigning an individual to govern a portion o data. The responsible person then coordinates the governance activities of other stakeholders.

- Data quality: is the optimization o data toward the desired state and orbits the question “What do you get compared with what you expected?”.

- Data modeling and design: is the process for converting data into a usable form.

- Data lineage: describes the recording of an audit trail of data through its lifecycle, tracking both the systems that process the data and the upstream data it depends on.

- Data integration and interoperability: is the process of integrating data across tools and processes.

- Data lifecycle management: First, data is increasingly stored in the cloud. This means we have pay-as-you-go storage costs instead of large up-front capital expenditures for an on-premises data lake. Second, privacy and data retention laws such as the GDPR and the CCPA require data engineers to actively manage data destruction to respect users’ “right to be forgotten.”

- Ethics and privacy: Data impacts people

DataOps has 3 core technical elements: automation, monitoring and observability, and incident response.

- Automation: allow data engineers to quickly deploy new product features and improvements to existing workflows.

- Observability and monitoring: monitoring, logging, alerting, and tracing.

- Incident response: using automation and observability capabilities to rapidly identify root causes of an incident and resove it as reliably and quickly as possible.

[Important] Data Architecture

- A data engineer should first understand the needs of the business and gather requirements for new use case.

- Next, a data engineer needs to translate those requirements to design new ways to capture and serve data, balanced for cost and operational simplicity. This means knowing the trade-offs with design patterns, technologies, and tools in the source systems, ingestion, storage, transformation, and serving data.

Orchestration

- Orchestration is the process of coordinating many jobs to run as quickly and efficiently as possible on the scheduled cadence. Apache Airflow is a schedulers, this is not accurate. A pure scheduler, is aware only of time; an orchestration engin builds in meta data on job dependencies, generally in form of DAG which can be run once or scheduled to run at a fixed interal of daily, weeekly, every hour, every five mins.

Software Engineering

- Core data processing code: Whether in ingestion, transformation, or data serving, data engineers need to be highly proficient and productive in frameworks and languages such as Spark, SQL, or Beam; we reject the notion that SQL is not code. t’s also imperative that a data engineer understand proper code-testing methodologies, such as unit, regression, integration, end-to-end, and smoke.

- Development of OS frameworks.

- Streaming: Engineers must also write code to apply a variety of windowing methods. Windowing allows real-time systems to calculate valuable metrics such as trailing statistics. Engineers have many frameworks to choose from, including various function platforms (OpenFaaS, AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Func‐ tions) for handling individual events or dedicated stream processors (Spark, Beam, Flink, or Pulsar) for analyzing streams to support reporting and real-time actions.

- Infrastructure as code.

- Pipelines as code.

- General-purpose problem solving.

3. Designing Good Data Architecture

Good data architecture provides seamless capabilities across every step of the data lifecycle and undercurrent. We will discuss about the components, batch patterns (data warehouses, data lakes), streaming patterns, and patterns that unify batch and streaming.

[Important] What is Data Architecture?

Successful data engineering is built upon rock-solid data architecture. We will review a few popular architecture approaches and frameworks.

Enterprise Architecture Defined

- Enterprise architecture is the design of systems to support change in the enterprise, achieved by flexible and reversible decisions reached through careful evaluation of trade-off.

- Architects are not simply mapping out IT processes and vaguely looking toward a distant, utopian future. They actively solve business problems and create new opportunities. Technical solutions exist not for their own sake but in support of business goals. Architects identify problems in the current state (poor data quality, scalability limits, money-losing lines of business), define desired future states (agile data-quality improvement, scalable cloud data solutions, improved business processes), and realize initiatives through execution of small, concrete steps

Data Architecture Defined

- Data architecture is the design of systems to support the evolving data needs of an enterprise, achieved by flexible and reversible decisions reached through a careful evaluation of trade-offs.

- What business processes does the data serve?

- How does the organization manage data quality?

- What is the latency requirement from when the data is produced to when it becomes avaialble to query?

- How will you move 10TB of data every hour from a source database to your data lake.

- Data architecture = Operational + Technical

- Operational architecture describe what nees to be done.

- Technical architecture details how it will happen.

“Good” Data Architecture

- Good data architecutre serves business requirements with a common, widely reusable set of building blocks while maintaining flexibility and making appropriate trade-off.

Principles of Good Data Architecutre

This is a 10000-foot view of good architecture, borrowed from AWS Well-Architected Framework andd Google Cloud’s Five Principles for Cloud-Native Architecture

AWS Well-Architected Framework

- Operational excellence.

- Security.

- Reliability.

- Performance efficiency.

- Cost optimization.

- Sustainability.

Google Cloud’s Five Principles for Cloud-Native Architecture

- Design for automation.

- Be smart with state.

- Favor managed services.

- Practice defense in depth.

- Always be architecting.

Additional principles:

- Choose common components wisely.

- Plan for failure.

- Architect for scalability.

- Architecture is leadership.

- Always be architecting.

- Build loosely coupled systems.

- Make reversible decisions.

- Prioritize security.

- Embrace FinOps.

Principle 1: Choose Common Components Wisely

- Common components can be anything that has broad applicability with an organization. Common components include object storage, version-control systems, observability, monitoring and orchestration systems, and processing engines.

Principle 2: Plan for Failure

- Availability: The percentage o time an IT service or component is in an operable state.

- Reliability: The system’s probability of meeting defined standards in performing its intended function during a specified intervals.

- Recovery time objective.

- Recovery point objective.

Principle 3: Architect for Scalability

- Scale up to handle significant quantities of data.

- Scale down to cut cost.

Principle 4: Architecture Is Leadership

- Data architects are responsible for technology decisions and architecture descriptions and disseminating these choices through effective leadership and tranining.

- An ideal data architect posses the technical skills of data enigneer but no longer practice data engineering day to day; they mentor curretn data engineers, make careful technology choice in consultation with their organization, and disseminate expertise through training and leadership. They train engineers in best practice and bring the company’s engineering resources together to pursue common goals in both technology and business.

Principle 5: Always Be Architecting

- The data architect maintains a target architecture and sequencing plans that change over time. The target architecture becomes a moving target, adjusted in response to business and technology changes internally and worldwide.

Principle 6: Build Loosely Coupled Systems

-

Putting data and services behind APIs enabled the loose coupling and eventually resulted in AWS as we know it now.

-

For software architecture, a loosely coupled system has the following properties:

-

- Systems are broken into many components.

-

- These systems interface with other services through abstraction layers, such as a messaging bus or an API. These abstraction layers hide and protect internal details of the service, such as a database backend or internal classes and method calls.

-

- As a consequence of property 2, internal changes to a system component don’t require changes in other parts. Details of code updates are hidden behind stable APIs. Each piece can evolve and improve separately.

-

- As a consequence of property 3, there is no waterfall, global release cycle for the whole system. Instead, each component is updated separately as changes and improvements are made.

-

-

Organizational characteristics:

-

- Many small teams engineer a large, complex system. Each team is tasked with engineering, maintaining, and improving some system components.

-

- These teams publish the abstract details of their componentsd to other teams via API definitions, message schemas,… Teams need not concern themselves with other teams’ components; they simply use the published API or message specifications to call these components. They iterate their part to improve their performance and capabilities over time. They might also publish new capabilities as they are added or request new stuff from other teams. Again, the latter happens without teams needing to worry about the internal technical details of the requested features. Teams work together through loosely couple communication.

-

- As a consequence of 2, each team can rapidly evolve and improve its component independently of the work of other teams.

-

- Specifically, 3 implies that team can release updates to their components with minal downtime. Teams release continuosly during regular working hours to make code changes and test them.

-

Principle 7: Make Reversible Decisions

- The decoupling / modularization of tech across your data architecture - always strive to pick the best-of-breed solutions that work for today

Principle 8: Prioritize Security

- Every data engineer must assume responsibility for the security of the systems they build and maintain. We focus now on two main ideas: zero-trust security and the shared responsibility security model. These align closely to a cloud-native architecture.

Principle 9: Embrace FinOps

- The term “FinOps” typically refers to the emerging professional movement that advo‐ cates a collaborative working relationship between DevOps and Finance, resulting in an iterative, data-driven management of infrastructure spending (i.e., lowering the unit economics of cloud) while simultaneously increasing the cost efficiency and, ultimately, the profitability of the cloud environment.

- In the cloud era, most data systems are pay-as-you-go and readily scalable. Systems can run on a cost-per-query model, cost-per-processing-capacity model, or another variant of a pay-as-you-go model.

Major Architecture Concepts

- Main goal of all architectures: to take data and transform it into something useful for downstream consumption.

Domains and Services

- Domain is a real-world subject are for which are you architecting.

- Service is a set of functionality whose goal is to accomplish a task.

- Identify what should go in the domain. When determining what the domain should encompass and what services to include, the best advice is to simply go and talk with users and stakeholders, listen to what they’re saying, and build the services that will help them do their job. Avoid the classic trap of architecting in a vacuum.

Distributed Systems, Scalability, and Designing for Failure

- Scalability: Allows us to increase the capacity of a system to improve performance and handle the demand.

- Elasticity: The ability of a scalable system to scale dynamically; a highly elastic system can automatically scale up and down based on the current workload.

- Availability: The percentage of time an IT service or component is in an operable state.

- Reliability: The system’s probability of meeting defined standards in performing its intended function during a specified interval.

Tight vs Loose Coupling: Tiers, Monoliths, and Microservices

- Tightly coupled: Every part of a domain and service is vitally dependent upon every other domain and service.

- Loose coupling: you have decentralized domains and services that do not have strict dependence on each other.

- Microservices: architecture comprises separate, decentralized, and loosely coupled services

Examples and Types of Data Architecture

Data Warehouse

- A data warehouse is a central data hub used for reporting and analysis.

Who’s Involved with Designing a Data Architecture?

Data architecture isn’t designed in a vacuum. Bigger companies may still employ data architects, but those architects will need to be heavily in tune and current with the state of technology and data.

Ideally, a data engineer will work alongside a dedicated data architect. However, if a company is small or low in its level of data maturity, a data engineer might work double duty as an architect. Because data architecture is an undercurrent of the data engineering lifecycle, a data engineer should understand “good” architecture and the various types of data architecture.

4. Choosing Technologies Across the Data Engineer Life Cycle

Team Size and Capabilities

There is a continuum of simple to complex technologies, and a team’s size roughly determines the amount of bandwidth your team can dedicate to complex solutions.

Speed to Market

In technology, speed to market wins. This means choosing the right technologies that help you deliver features and data faster while maintaining high-quality standards and security. It also means working in a tight feedback loop of launching, learning, iterating, and making improvements.

Deliver value early and often.

Interoperability

When choosing a technology or system, you’ll need to ensure that it interacts and operates with other technologies. Interoperability describes how various technologies or systems connect, exchange information, and interact.

Cost Optimization and Business Value

In a perfect world, you’d get to experiment with all the latest, coolest technologies without considering cost, time investment, or value added to the business. In reality, budgets and time are finite, and the cost is a major constraint for choosing the right data architectures and technologies.

Data engineers need to be pragmatic about flexibility. The data landscape is changing too quickly to invest in long-term hardware that inevitably goes stale, can’t easily scale, and potentially hampers a data engineer’s flexibility to try new things. Given the upside for flexibility and low initial costs, we urge data engineers to take an opex-first approach centered on the cloud and flexible, pay-as-you-go technologies.

Today vs. Future: Immutable Vs. Transitory Technology

In an exciting domain like data engineering, it’s all too easy to focus on a rapidly evolving future while ignoring the concrete needs of the present. The intention to build a better future is noble but often leads to overarchitecting and overengineering. Tooling chosen for the future may be stale and out-of-date when this future arrives; the future frequently looks little like what we envisioned years before.

Given the reasonable probability of failure for many data technologies, you need to consider how easy it is to transition from a chosen technology. What are the barriers to leaving? As mentioned previously in our discussion about opportunity cost, avoid “bear traps.” Go into a new technology with eyes wide open, knowing the project might get abandoned, the company may not be viable, or the technology simply isn’t a good fit any longer.

Location

Companies now have numerous options when deciding where to run their technol‐ ogy stacks. A slow shift toward the cloud culminates in a veritable stampede of companies spinning up workloads on AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

Build vs Buy

Build versus buy is an age-old debate in technology. The argument for building is that you have end-to-end control over the solution and are not at the mercy of a vendor or open source community. The argument supporting buying comes down to resource constraints and expertise; do you have the expertise to build a better solution than something already available.

Monolith Vs. Modular

Monoliths versus modular systems is another longtime debate in the software archi‐ tecture space. Monolithic systems are self-contained, often performing multiple func‐ tions under a single system.

Serverless vs. Servers

A big trend for cloud providers is serverless, allowing developers and data engineers to run applications without managing servers behind the scenes. Serverless provides a quick time to value for the right use cases. For other cases, it might not be a good fit.

Undercurrents and Their Impacts on Choosing Technologies

As seen in this chapter, a data engineer has a lot to consider when evaluating technol‐ ogies. Whatever technology you choose, be sure to understand how it supports the undercurrents of the data engineering lifecycle.

Citation

Cited as:

Fundamentals of Data Engineering: Foundation and Building Blocks https://mnguyen0226.github.io/posts/fundamentals_of_data_engineering_1/post/.

Or

@article{nguyen2023mtl,

title = "Fundamentals of Data Engineering: Foundation and Building Blocks",

author = "Nguyen, Minh",

journal = "mnguyen0226.github.io",

year = "2024",

month = "January",

url = "https://mnguyen0226.github.io/posts/fundamentals_of_data_engineering_1/post/"

}

References